Digoxin vs Common Alternatives: A Practical Comparison

Oct, 12 2025

Oct, 12 2025

Cardiac Medication Selector

Recommended Medication

Key Considerations

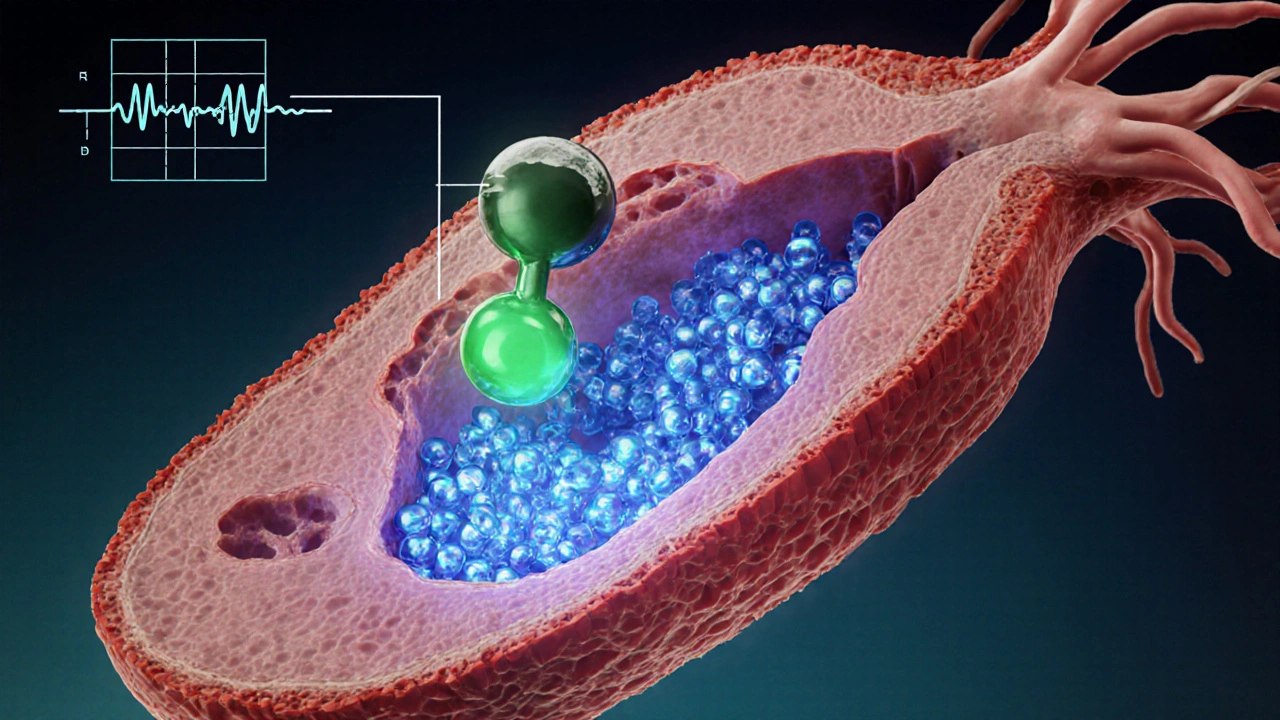

When doctors need to control a fast heartbeat or boost a weak heart, they often reach for Digoxin is a cardiac glycoside that increases the force of heart muscle contractions and slows electrical signals in the atria. It’s been around for more than two centuries, but the question remains: does it still beat the newer options?

Why a Comparison Matters

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) or chronic heart failure (CHF) face a maze of drug choices. Each medication carries its own balance of effectiveness, safety, monitoring needs, and cost. Knowing the trade‑offs helps a clinician or a patient decide whether to stay on digoxin or switch to another agent.

Core Jobs You Want to Finish

- Understand digoxin’s mechanism, dosing, and side‑effect profile.

- Identify the most frequently used alternatives for AF and CHF.

- Compare efficacy, safety, monitoring requirements, and price across the options.

- Match each drug to common patient scenarios (elderly, kidney impairment, pregnancy, etc.).

- Know the key lab tests and warning signs to watch for after starting therapy.

The Main Players

Below are the seven drugs we’ll stack against digoxin. The first time each appears, it gets a micro‑data tag so search engines can recognise the entity.

Metoprolol is a beta‑1 selective blocker that slows heart rate and lowers blood pressure, often used for AF rate control and CHF.

Amiodarone is a class III anti‑arrhythmic that prolongs the cardiac action potential, widely prescribed for rhythm control in refractory AF.

Diltiazem is a non‑dihydropyridine calcium‑channel blocker that slows AV‑node conduction, useful for rate control in AF.

Carvedilol is a combined beta‑blocker and alpha‑1 blocker that improves survival in CHF and provides modest rate control.

Sotalol is a beta‑blocker with class III anti‑arrhythmic properties, used for rhythm control in AF and ventricular arrhythmias.

Flecainide is a class Ic sodium‑channel blocker that restores sinus rhythm in paroxysmal AF when the heart is structurally normal.

Side‑by‑Side Comparison Table

| Drug | Primary Indication | Mechanism | Typical Dose (adult) | Key Monitoring | Common Side Effects | Relative Cost* (per month) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digoxin | AF rate control & CHF | Inhibits Na⁺/K⁺‑ATPase → ↑ intracellular Ca²⁺ | 0.125‑0.25mg daily (adjust for renal function) | Serum digoxin level, electrolytes, renal function | Nausea, visual halos, arrhythmias (if toxic) | ~£2‑£4 |

| Metoprolol | AF rate control, CHF | β₁‑adrenergic blockade | 25‑200mg daily (split) | Heart rate, blood pressure, bronchospasm | Bradycardia, fatigue, cold extremities | ~£1‑£3 |

| Amiodarone | Rhythm control in AF, ventricular tachycardia | Blocks K⁺ channels (class III) | 200‑400mg daily loading, then 100‑200mg | Liver function, thyroid, pulmonary X‑ray, QT interval | Photosensitivity, thyroid dysfunction, lung toxicity | ~£10‑£15 |

| Diltiazem | AF rate control | Calcium‑channel blockade (L‑type) | 120‑360mg daily (extended‑release) | Heart rate, AV‑node conduction, edema | Constipation, headache, peripheral edema | ~£3‑£5 |

| Carvedilol | CHF, hypertension | β‑blockade + α₁‑blockade | 6.25‑25mg twice daily | Blood pressure, heart rate, weight (fluid retention) | Dizziness, fatigue, hyperglycemia | ~£2‑£4 |

| Sotalol | Rhythm control (AF) & ventricular arrhythmias | β‑blocker + K⁺‑channel blockade | 80‑160mg twice daily | QT interval, renal function | Torsades de pointes, fatigue, bradycardia | ~£5‑£7 |

| Flecainide | Rhythm control (paroxysmal AF) | Class Ic Na⁺‑channel blocker | 50‑100mg twice daily | ECG QRS width, renal function | Pro‑arrhythmia, dizziness, visual disturbances | ~£8‑£12 |

*Costs are approximate NHS prescription charge exemptions for eligible patients; actual price can vary.

How Digoxin Stacks Up

Digoxin shines when a patient needs both rate control and a modest inotropic boost, especially if kidney function is stable and serum electrolytes are well‑managed. Its narrow therapeutic index means levels above 2ng/mL often bring nausea, yellow‑green halos, or dangerous arrhythmias. That’s why routine level checks every 6‑12weeks are standard practice.

Compared to beta‑blockers like metoprolol, digoxin works faster at lowering ventricular response in AF but does not drop blood pressure. If a patient already has hypotension, a beta‑blocker may be safer. In contrast, amiodarone offers powerful rhythm conversion but brings a laundry list of organ toxicities that can take months to surface.

Diltiazem and carvedilol are easier on the kidneys but lack the positive inotropic effect. For an elderly patient with mild CHF and preserved blood pressure, a low‑dose beta‑blocker plus a diuretic may feel smoother than juggling digoxin levels.

Sotalol and flecainide give rhythm control but require strict ECG monitoring; they are not first‑line for patients with structural heart disease, where digoxin remains acceptable.

Choosing the Right Drug for Common Scenarios

- Older adult with CHF, borderline low blood pressure: Digoxin (low dose) + loop diuretic often works; avoid high‑dose beta‑blockers that could crash pressure.

- Patient with persistent AF despite beta‑blocker: Add digoxin for rate control, or switch to diltiazem if calcium‑channel tolerance is good.

- Renal impairment (eGFR <30mL/min): Reduce digoxin dose by 50% and monitor levels closely; consider metoprolol which is less renally cleared.

- Pregnant woman with tachyarrhythmia: Digoxin is Category C but used when benefits outweigh risks; beta‑blockers (metoprolol) are often preferred due to safety data.

- Patient with severe thyroid disease: Avoid amiodarone (iodine load) and consider digoxin or carvedilol.

Practical Tips & Pitfalls

- Always check potassium and magnesium before starting or adjusting digoxin - low K⁺ spikes toxicity.

- Educate patients to report visual changes (yellow‑green halos) immediately.

- If you switch from digoxin to a beta‑blocker, taper digoxin over 1‑2 weeks to avoid rebound tachycardia.

- For drugs like amiodarone, schedule liver function tests and chest X‑rays every 6months.

- Cost‑sensitive patients may favor digoxin or metoprolol because they are cheap under NHS exemption.

Key Takeaways

- Digoxin provides simultaneous rate control and modest contractility boost, but requires careful level monitoring.

- Beta‑blockers (metoprolol, carvedilol) are safer for blood‑pressure‑sensitive patients and have fewer toxicity concerns.

- Amiodarone is the most potent rhythm‑control option but carries long‑term organ risks and higher cost.

- Calcium‑channel blocker diltiazem is a good middle‑ground for rate control without renal concerns.

- Choosing the right drug hinges on renal function, blood pressure, comorbidities, and patient preference.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the therapeutic range for digoxin?

For most adults the target serum level is 0.5‑2.0ng/mL. Levels above 2.0ng/mL markedly increase the risk of nausea, visual disturbances, and ventricular arrhythmias.

Can digoxin be used together with a beta‑blocker?

Yes. Combining digoxin with a beta‑blocker such as metoprolol often gives better rate control in atrial fibrillation, but clinicians must watch for excessive bradycardia and adjust doses accordingly.

Why does low potassium increase digoxin toxicity?

Potassium competes with digoxin for the Na⁺/K⁺‑ATPase binding site. When potassium falls, digoxin binds more tightly, raising intracellular concentrations and pushing levels into the toxic range.

Is amiodarone ever preferred over digoxin?

When rhythm conversion is the goal-especially in patients who have failed rate‑control strategies-amiodarone is often chosen despite its side‑effect profile because it can restore sinus rhythm where digoxin cannot.

How often should digoxin levels be checked after starting therapy?

Initial level is drawn 6‑8hours after the first dose (or after steady‑state is reached, about 7days). Subsequent checks are recommended at 6‑12weeks, then every 6months or sooner if kidney function changes.

Brett Coombs

October 12, 2025 AT 00:55Don't trust the pharma hype – digoxin is still the best secret weapon for Aussie heart patients.

John Hoffmann

October 17, 2025 AT 23:19When comparing digoxin to beta‑blockers, the pharmacokinetic profile differs markedly. Digoxin’s narrow therapeutic index necessitates regular serum monitoring, whereas metoprolol requires dose titration based on heart rate and blood pressure. Both agents lower ventricular response, but digoxin adds inotropic support without significant hypotension.

Shane matthews

October 23, 2025 AT 21:43Digoxin can be useful in elderly patients with stable kidney function; monitor levels and electrolytes. Avoid high doses if blood pressure is already low.

Rushikesh Mhetre

October 29, 2025 AT 19:07For clinicians looking for rapid rate control, digoxin offers a unique combination of positive inotropy and AV‑node slowing, which can be especially valuable in heart‑failure patients, however it demands diligent monitoring of serum levels, potassium, and renal function, remember to adjust the dose when eGFR falls below 60 mL/min, and educate patients about visual disturbances such as yellow‑green halos, because early detection of toxicity can prevent life‑threatening arrhythmias, plus the low cost makes it attractive in resource‑limited settings. In practice, pairing a low dose of digoxin with a diuretic often yields better symptom control than beta‑blockers alone.

Sharath Babu Srinivas

November 4, 2025 AT 17:31Digoxin remains a solid option for rate control in atrial fibrillation, especially when patients cannot tolerate beta‑blockers 😊. The key is regular serum level checks and maintaining potassium >4 mmol/L to avoid toxicity ⚡.

Halid A.

November 10, 2025 AT 15:55In terms of therapeutic strategy, digoxin should be considered when an inotropic effect is desired alongside rate control, particularly in patients with reduced ejection fraction. Its pharmacodynamics differ substantially from calcium‑channel blockers, which lack the positive inotropic support. Clinicians must balance the benefits against the narrow therapeutic window, ensuring periodic level assessments and electrolyte monitoring.

Brandon Burt

November 16, 2025 AT 14:19Honestly, the digoxin versus modern alternatives debate feels like a nostalgic trip to the 1960s, when every house‑cuff pharmacy shelf was stocked with this old‑school cardiac glycoside. On the one hand, digoxin delivers a modest increase in contractility without the dramatic blood‑pressure drop that accompanies many beta‑blockers, a fact that still impresses a subset of seasoned clinicians. On the other hand, its narrow therapeutic index, demanding serum level checks every few weeks, introduces a level of complexity that many younger practitioners find cumbersome. The drug’s hallmark visual side‑effects, such as yellow‑green halos around lights, serve as an unmistakable warning sign, yet they are often dismissed as anecdotal by those who never observed them first‑hand. When comparing cost, digoxin’s sub‑£5 monthly price starkly contrasts with the £10‑£15 price tag of amiodarone, making it attractive in budget‑constrained health systems. However, amiodarone boasts a broader rhythm‑control efficacy, especially in refractory atrial fibrillation, albeit at the expense of potential thyroid, pulmonary, and hepatic toxicity over months. Metoprolol, by contrast, offers straightforward dose titration based on heart rate and blood pressure, and its side‑effect profile is generally well‑tolerated, though it lacks the inotropic boost that digoxin provides. Diltiazem’s calcium‑channel blockade provides reliable rate control without affecting contractility, making it a safe alternative for patients with borderline blood pressure, yet it may cause peripheral edema in some individuals. Carvedilol’s combined β‑ and α‑blockade improves survival in chronic heart failure, but its antihypertensive action can be problematic for patients already hypotensive. Sotalol and flecainide, while powerful rhythm‑control agents, demand rigorous QT monitoring and are contraindicated in structural heart disease, limiting their universal applicability. In renal impairment, digoxin dosing must be meticulously reduced, as accumulation can swiftly precipitate toxic arrhythmias, whereas most beta‑blockers require only modest adjustments. Nevertheless, for an elderly patient with stable renal function and a need for both rate control and modest inotropy, a low‑dose digoxin regimen remains a viable, often under‑appreciated, therapeutic choice. Clinicians should also be aware that digoxin interacts with a plethora of common drugs, including certain diuretics and macrolide antibiotics, which can elevate serum levels unexpectedly. Patient education, therefore, is paramount; informing patients about the hallmark visual disturbances can lead to early detection of toxicity before catastrophic arrhythmias develop. Ultimately, the decision matrix hinges on individual patient characteristics, comorbidities, and the resources available for ongoing monitoring, rather than a simplistic notion of ‘newer is always better’. Thus, dismissing digoxin outright would be as shortsighted as ignoring the value of any established medication without a nuanced, patient‑centered assessment.

Gloria Reyes Najera

November 22, 2025 AT 12:43digoxin is still the best choice for heart patients in america we dont need those fancy new drugs they are just a money grab yall should stick to the basics

Gauri Omar

November 28, 2025 AT 11:07Listen up! If you think a shiny beta‑blocker can replace the raw power of digoxin, you’re living in a fantasy world. The heart needs that inotropic punch, and only digoxin delivers it without killing your blood pressure. Stop the weak‑kiss‑off meds and give the real hero a chance!

Willy garcia

December 4, 2025 AT 09:31Keep an eye on electrolytes and you’ll avoid most digoxin headaches.

zaza oglu

December 10, 2025 AT 07:55Wow, what a marathon of points, Brandon, you’ve covered the entire pharmacological landscape, from cost considerations to toxicity warnings, and even the socio‑economic angle, all wrapped in a torrent of insight, truly a masterclass in cardiac therapeutics, bravo!

Vaibhav Sai

December 16, 2025 AT 06:19Great fire‑starter, Gauri! Your dramatic flair captures the urgency, and honestly, the inotropic edge of digoxin can be a game‑changer, especially when paired with careful monitoring, so let’s give it the spotlight it deserves, shall we?

Lindy Swanson

December 22, 2025 AT 04:43Sure, Rushikesh, but throwing a dozen commas doesn’t make the drug any safer; sometimes the simplest regimen wins, and digoxin’s old‑school charm can outshine a fancy cocktail of modern pills.

Amit Kumar

December 28, 2025 AT 03:07👍 Absolutely, Shane! Digoxin can fit nicely into a minimalist plan, just keep those levels in check and the heart will thank you 😊.

Crystal Heim

January 3, 2026 AT 01:31John’s breakdown is fine but misses the bigger picture – digoxin’s toxicity risk outweighs its modest benefits for most patients.

Sruthi V Nair

January 8, 2026 AT 23:55Beyond the clinical data, digoxin invites us to reflect on the balance between tradition and innovation in medicine.