How Anticoagulant Medications Prevent Blood Clots

Oct, 22 2025

Oct, 22 2025

Anticoagulant Bleeding Risk Calculator

HAS-BLED Bleeding Risk Assessment

This tool calculates your HAS-BLED bleeding risk score, a clinically validated tool used to assess bleeding risk in patients taking anticoagulants. Higher scores indicate greater bleeding risk.

Bleeding Risk Results

Has-Bled Score:

- For scores 3 or higher: Consider additional monitoring and risk-reduction strategies with your healthcare provider

- Maintain regular INR checks if on warfarin

- Avoid NSAIDs and other blood-thinning medications

- Carry medical alert information

Quick Takeaways

- Anticoagulant medications slow down the clotting cascade, not the platelets.

- Three main groups dominate today: vitamin K antagonists, heparin products, and direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs).

- Choosing the right drug depends on the clot‑risk condition, kidney function, and how closely you can be monitored.

- Bleeding is the biggest trade‑off; knowing drug‑specific risks helps you and your clinician manage them.

- Lifestyle tweaks (exercise, hydration, avoiding certain foods) boost drug effectiveness and safety.

What Exactly Is a Blood Clot?

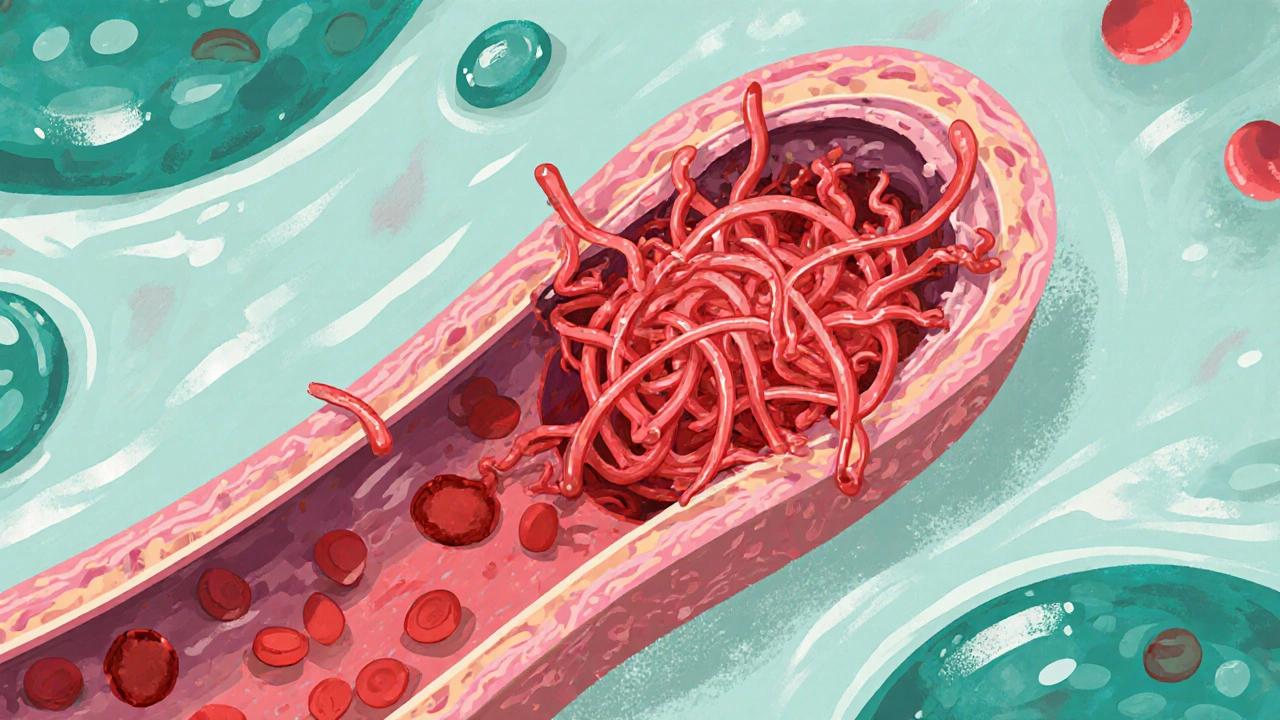

Blood clot is a semi‑solid mass of fibrin, red cells, and platelets that forms when the coagulation system over‑reacts to injury or inflammation. In healthy people, clotting seals off bleeding vessels and then dissolves once healing is complete. Problems arise when clots form inside uninjured vessels - they can block blood flow to the brain, lungs, or legs, leading to stroke, pulmonary embolism, or deep‑vein thrombosis (DVT). The body’s clotting cascade involves dozens of proteins, and a tiny slip‑up can tip the balance toward dangerous blockage.

How Anticoagulant Medications Work

Anticoagulant medication is a drug class that interferes with specific steps of the clotting cascade, slowing the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. Unlike antiplatelet agents (which stop platelets from sticking together), anticoagulants target enzymes like thrombin (Factor IIa) or Factor Xa. By reducing the speed at which fibrin strands form, the medication gives the body’s natural fibrinolytic system a chance to break down any premature clots before they become hazardous.

The main mechanisms are:

- Inhibiting vitamin K recycling: Vitamin K is essential for producing clotting factors II, VII, IX, and X. Blocking its action reduces those factors.

- Enhancing antithrombin activity: Heparin binds antithrombin, which then deactivates thrombin and Factor Xa.

- Directly blocking Factor Xa or thrombin: DOACs sit in the active site of the enzyme, preventing it from converting pro‑thrombin to thrombin.

Major Anticoagulant Families

The three families dominate modern practice. Below is a quick rundown of each, followed by a detailed comparison table.

Warfarin is a long‑standing vitamin K antagonist that has been used for more than 60 years. It works by blocking the enzyme that recycles vitamin K, which in turn lowers the levels of vitamin K‑dependent clotting factors. The drug requires regular blood‑test monitoring (INR) and dietary caution because foods rich in vitamin K (leafy greens) can blunt its effect.

Heparin (including low‑molecular‑weight heparin, LMWH) is administered by injection and instantly boosts antithrombin activity. It’s often used in hospitals for rapid anticoagulation, especially during surgeries or in patients with acute DVT/PE. Monitoring is less intense than warfarin, but renal function must be considered for LMWH.

Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) such as apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and edoxaban directly inhibit Factor Xa or thrombin. They are taken by mouth, need little to no routine blood testing, and have predictable dosing. However, they are cleared by the kidneys, so dose adjustments are required in renal impairment.

| Class | Typical Drugs | Primary Mechanism | Administration | Monitoring Needed? | Key Side‑Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin K Antagonist | Warfarin | Blocks vitamin K recycling → ↓ Factors II, VII, IX, X | Oral | Yes - INR 2‑3 (or 2‑3.5 for some indications) | Bleeding; skin necrosis if INR drops too low |

| Heparin (Unfractionated / LMWH) | Heparin, Enoxaparin | Enhances antithrombin → ↓ Thrombin & Factor Xa | Injectable (IV or sub‑Q) | Usually no routine test (aPTT for UFH only) | Heparin‑induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) |

| Direct Oral Anticoagulant | Apixaban, Rivaroxaban, Dabigatran, Edoxaban | Directly blocks Factor Xa (or thrombin for dabigatran) | Oral | Rarely - specific assays in special cases | Gastro‑intestinal bleeding; renal dose issues |

When Do Doctors Prescribe Anticoagulants?

Anticoagulants aren’t a one‑size‑fits‑all. Clinicians weigh the patient’s clot‑risk condition against bleeding risk. Common scenarios include:

- Atrial fibrillation (AFib): The irregular heartbeat can throw clots from the atria into the brain, causing stroke. CHA₂DS₂‑VASc scoring helps decide if an anticoagulant is needed.

- Deep‑vein thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE): Immediate anticoagulation prevents clot propagation and new clot formation.

- Post‑surgical prophylaxis: After orthopedic procedures (hip/knee replacement), patients receive a short course of anticoagulant to avoid post‑op DVT.

- Inherited clotting disorders (e.g., Factor V Leiden): Long‑term anticoagulation may be considered if a personal or family history of thrombosis exists.

In each case, the doctor reviews renal and hepatic function, drug interactions, and patient preference before picking a regimen.

Balancing Benefits and Bleeding Risks

Bleeding is the most dreaded complication. The risk varies by drug:

- Warfarin carries a higher intracranial‑bleed rate, especially when INR exceeds the therapeutic window.

- Heparin rarely causes major bleeding but can trigger HIT, a paradoxical clotting disorder.

- DOACs generally have lower intracranial‑bleed risk than warfarin but may increase gastrointestinal bleeding, particularly with dabigatran.

Doctors use scoring tools like HAS‑BLED to estimate bleeding risk before starting therapy. Patient education-recognizing signs of bleeding, avoiding NSAIDs, and proper medication storage-helps mitigate hazards.

Practical Tips for Patients on Anticoagulants

- Keep a medication list. Include dose, timing, and any recent labs (INR, kidney function).

- Follow diet guidelines. If you’re on warfarin, maintain a consistent intake of leafy greens; don’t swing from high‑vitamin K meals to none.

- Watch for drug interactions. Antibiotics, antifungals, and some heart meds can boost or reduce anticoagulant effect.

- Stay hydrated. Dehydration can concentrate blood and raise clot risk, especially during travel.

- Report unusual bruising or dark stools. Early detection prevents serious bleeding.

- Carry a medical alert card. In emergencies, first responders need to know you’re anticoagulated.

Future Directions: New Anticoagulants on the Horizon

Research continues to chase the perfect balance: strong clot prevention with minimal bleeding. Some promising avenues include:

- Factor XI inhibitors: Early trials show they block clot formation without significantly impacting normal hemostasis, suggesting a lower bleeding profile.

- RNA‑based anticoagulants: Targeting the genetic instructions for clotting factors could allow dose titration via short‑acting molecules.

- Reversal agents for DOACs (e.g., andexanet alfa for Factor Xa inhibitors) are becoming more accessible, easing clinician concerns about uncontrolled bleeding.

These innovations may expand anticoagulant use to patients who are currently deemed too high‑risk for existing drugs.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I stop my anticoagulant if I feel fine?

No. Anticoagulants work continuously to keep clots from forming. Stopping early raises the chance of stroke, DVT, or PE, even if you feel well.

Do I need regular blood tests with DOACs?

Usually not. DOACs have predictable pharmacokinetics, so routine labs aren’t required unless you have kidney disease or are undergoing surgery.

What foods should I avoid with warfarin?

Maintain a steady amount of vitamin K‑rich foods (like kale, spinach, broccoli). Sudden spikes or drops can swing your INR out of range.

Is it safe to take NSAIDs while on anticoagulants?

Generally avoid them. NSAIDs increase gastric bleeding risk and can further impair platelet function, compounding anticoagulant effects.

How quickly does heparin work compared to warfarin?

Heparin acts within minutes after IV injection, making it ideal for emergencies. Warfarin takes 2‑5 days to reach therapeutic levels.

Understanding how anticoagulant medications block clot formation empowers you to work with your doctor, keep risks low, and stay active. Whether you’re on a pill, an injection, or a future gene‑edited therapy, the goal stays the same: stop dangerous clots without turning you into a walking bleed.

Iris Joy

October 22, 2025 AT 20:49Anticoagulants are a lifesaver for anyone at risk of clotting, but they’re not a “set‑and‑forget” pill. Keep an eye on your diet, especially if you’re on warfarin-leafy greens can swing your INR like a pendulum. Regular check‑ups let your doc fine‑tune the dose before a bleed pops up. Staying hydrated and moving around on long trips cuts down the chance of a hidden clot forming in your legs. And always carry a medical alert card so emergency crews know you’re on blood thinners.

Jai Reed

October 29, 2025 AT 18:29STOP ignoring the INR trends-your numbers can jump from safe to dangerous overnight. If you miss a test, you’re gambling with brain bleeding. Adjust your diet consistently; a single kale binge can nullify weeks of warfarin work. Talk to your provider ASAP when you notice any bruising or black stools.

WILLIS jotrin

November 5, 2025 AT 17:09It’s fascinating how the body balances clotting and bleeding, almost like a tightrope walk. Anticoagulants tip the scale just enough to keep the rope from snapping under pressure. Think of them as a gentle reminder that our circulatory system is constantly negotiating. When you pair the meds with lifestyle tweaks, you’re essentially coaching your veins to stay calm.

Joanne Ponnappa

November 12, 2025 AT 15:49Great rundown! 👍 Knowing when to use each class makes the whole process less scary. 😊

Michael Vandiver

November 19, 2025 AT 14:29Totally agree! The tables really help visualise dosing differences 😎 keep that info handy next time you chat with your doc 👍

Emily Collins

November 26, 2025 AT 13:09Do not think you’re invincible while on blood thinners.

Rachael Turner

December 3, 2025 AT 11:49Anticoagulant therapy is not just a prescription line; it’s a partnership between you and your healthcare team.

You first need to understand why your doctor chose a particular drug, whether it’s warfarin, a heparin product, or a newer DOAC.

Each class works on a different step of the clotting cascade, and that nuance dictates monitoring frequency.

Warfarin, for example, demands regular INR checks because its effect can swing wildly with vitamin K intake.

Heparin, especially low‑molecular‑weight versions, is given by injection and often doesn’t need daily labs but requires dose adjustment in kidney disease.

DOACs shine with predictable dosing and minimal blood work, yet they hide a vulnerability in patients with impaired renal function.

The real art lies in balancing clot‑prevention benefits against the ever‑present bleeding risk that all anticoagulants share.

Tools like CHA₂DS₂‑VASc and HAS‑BLED give you a snapshot of stroke versus bleed probability, but they’re only guides, not absolutes.

Lifestyle factors-like staying hydrated on long flights, avoiding excess alcohol, and keeping a consistent diet-can tilt the scales toward safety.

Carrying a medical alert card or wearing a bracelet ensures that emergency responders know you’re on an anticoagulant before they administer other meds.

If you notice any unusual bruising, dark stools, or prolonged nosebleeds, call your clinician immediately; early intervention can prevent a catastrophic bleed.

For those on warfarin, a sudden change in leafy‑green consumption can push your INR out of range, so a steady diet is crucial.

Meanwhile, patients on DOACs should be mindful of over‑the‑counter NSAIDs, which amplify gastrointestinal bleeding risk.

In the future, factor XI inhibitors and RNA‑based therapies may offer clot protection with even fewer bleeding events, but they’re not widely available yet.

Until those hit the market, the best strategy is to stay informed, keep your appointments, and treat your medication as a daily habit that safeguards your health.

Suryadevan Vasu

December 10, 2025 AT 10:29When renal function declines, dose reduction of DOACs becomes mandatory; otherwise drug accumulation raises bleed risk sharply. Monitor creatinine clearance at least annually to stay within safe limits. Adjust the regimen promptly if eGFR falls below the recommended threshold.

Bret Toadabush

December 17, 2025 AT 09:09They dont want you to know that the pharma giants control the data on bleeding stats. Every time a new anticoagulant hits the market, the same old side‑effects get buried under glossy ads. Dont trust the hype-ask for raw trial numbers before you sign up for any pill.

Diane Thurman

December 24, 2025 AT 07:49Seriously, if you cant keep a simple med list you shouldn't be on warfarin. Most of the bleeds happen because people ignore diet warnings. Get your act together and follow the doc's orders.